Return to Mega Movie Pages Plus

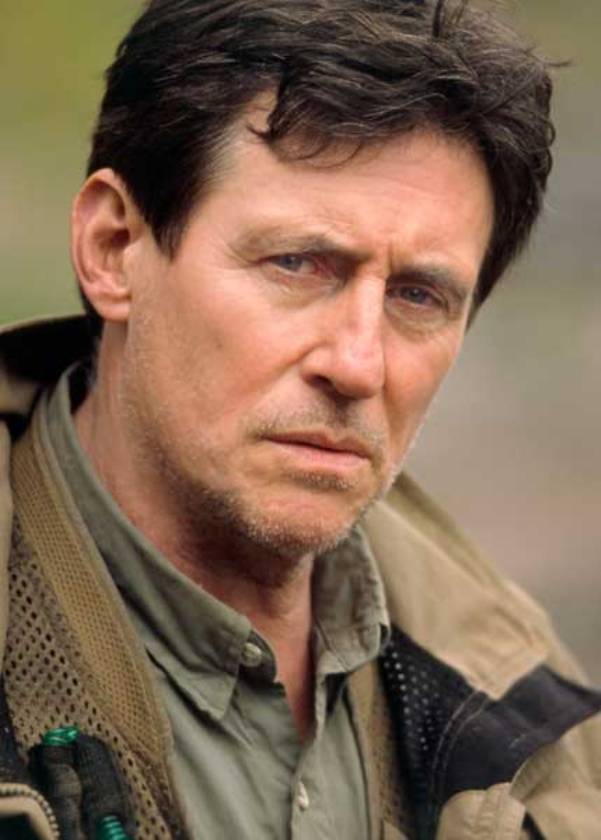

role

Stewart Kane

production

Directed by Ray Lawrence

Screenplay by Beatrix Christian, based on the short story “So Much Water So Close to Home,” by Raymond Carver

April Films, 2006

Filmed on location at Jindabyne, New South Wales, Australia

Received a 65% fresh rating at Rotten Tomatoes and a score of 65 (generally favorable reviews) at MetaCritic

tagline

Under the surface of every life lies a mystery

In Australia, the town of Jindabyne is about to face a moment of truth

synopsis

On an annual fishing trip, in isolated high country, Stewart, Carl, Rocco and Billy (‘the Kid’) find a girl’s body in the river. It’s too late in the day for them to hike back to the road and report their tragic find. The next morning, instead of making the long trek back, they spend the day fishing. Their decision to stay on at the river is a little mysterious—almost as if the place itself is exerting some kind of magic over them. When the men finally return home to Jindabyne, and report finding the body, all hell breaks loose. Their wives can’t understand how they could have gone fishing with the dead girl right there in the water—she needed their help. The men are confused—the girl was already dead, there was nothing they could do for her.

Stewart’s wife Claire is the last to know. As details filter out, and Stewart resists talking about what has happened, she is unnerved. There is a callousness about all of this which disturbs her deeply. Stewart is not convinced that he has done anything wrong. Claire’s faith in her relationship with her husband is shaken to the core.

The fishermen, their wives and their children are suddenly haunted by their own bad spirits. As public opinion builds against the actions of the men, their certainty about themselves and the decision they made at the river is challenged. They cannot undo what they have done.

Only Claire understands that some-thing fundamental is not being addressed. She wants to understand and tries to make things right. In her determination Claire sets herself not only against her own family and friends but also those of the dead girl. Her marriage is taken to the brink and her peaceful life with Stewart and their young son hangs in the balance.–from the official website

trailer in HD

video interview with Gabriel Byrne

promotional images

More promotional stills are in the Gallery.

quotes

[Father and son are fishing in Jindabyne Lake when Tom catches a clock]

Stewart: Wow, that’s a funny looking fish.

Tom: It’s a piece of junk.

Stewart: It’s a clock fish.

Stewarts’ mother (upon seeing his newly darkened hair): That hair makes you look like the kind of man who visits prostitutes.

—

[At the dinner on the eve of the fishing trip]

Stewart: (raising his glass to all): In a hidden valley–

Everyone (laughing): Here we go, here we go!

Stewart: Lies a hidden river–

Carl: Full of blarney (laughter).

Stewart: There dwells a fish, wild and cunning. A mysterious, wild… (pauses)

Claire: Stay with it! (much laughter). Baby, stay with it!

Stewart: Mysterious, wild fish, ancient, immemorial as time, lies waiting–

Carl: As we are all doing (laughter).

Stewart: Waiting for us. I knew this piece last year. Anyway, to the wild one!

Rocco: You’re out of condition, old man.

Stewart: No, I’m not. Someone just moved the river, that’s all.—

Stewart: You think we did the wrong thing by that girl?

Carl: She didn’t care what we did. She’s got no opinion, no feelings one way or the other. She’s dead.

[Stewart and Claire are talking to Tom before he goes to sleep]

Tom: Was it scary?

Stewart: No. Sad.

Tom: What did the dead lady look like?

Stewart: She looked like she was…she was asleep.

Tom: Caylin-Calandria says she has no clothes on.

Stewart: Caylin-Calandria doesn’t know as much as she thinks she knows.

Tom: Was the dead lady under the water where it’s deep?

Claire: Your dad took her out of the water and he wrapped her up in a sleeping bag and he made her all nice and warm and cozy.

Tom: (to his father): Caylin-Calandria says there’s a serial killer. She says he’s coming after you.

Stewart: Now listen. You don’t pay any attention to what anyone says, no matter what they say. The river is a long, long way away and there are no bad men here, okay? Now go to sleep.—

Stewart: I didn’t want to upset you. I thought it could wait ’til morning.

Claire: What really happened out there?

Stewart: I told you. Nothing happened. We just got stuck, that’s all. Jeez, I don’t know what all the fuss is about, I really don’t.

Claire: What if it had been Tom in the water?

Stewart: But it wasn’t Tom. It was a stranger.

Stewart: I just want you to be okay. That’s all. Jesus, I’m sorry I mentioned it.

Claire (whispering): Last night. How could you have touched me like that. After finding her?

Stewart: Claire, I am so exhausted.

Claire: She needed your help.

Stewart: She didn’t need my help. She was beyond help. There was nothing anybody could do for her.

[Claire leaves the room]—

Claire: What if you’d found a boy in the river? Wouldn’t you have taken him out and covered him up?

Stewart: What? What are you talking about?

Claire: You don’t know?

Stewart: No, no, I don’t know what you’re talking about. I don’t know where you’re going with this. You’re not making any sense.

Claire: Course not. That’s because I’m the unstable one.

Stewart: Well, let’s face it, you’re not exactly behaving rationally.

(Claire throws her coffee in his face)

Claire: Aren’t I!?

Stewart (after setting his own broken nose straight again): See? You do it while the adrenaline’s still pumping. That way, you don’t feel a thing…

interview from official website

Interview with Gabriel Byrne

What is “Jindabyne” about?

The story is about four men who come upon the body of a woman in the river and, not out of any sense of badness or lack of feeling, decide to leave the body in the river and not report it to the police until they get back from their fishing trip. Like many situations that we find ourselves in, in life, we’re unaware of the consequences of our actions until those consequences come home to visit us in all kinds of unexpected ways. So the film is really about how this incident haunts these men and the lives of the people who are closest to them.

Tell us about Stewart, the character you play.

Stewart is a working-class, ordinary man who owns a garage. He used to be a rally driver and he has given up that life to become settled in this community. Not a simple man, but a man who lives a pretty simple predictable life up until this moment. As a result of this incident he’s forced to examine who he really is morally, emotionally, and socially. Stewart and Claire have had their troubles like any couple in a long- term relationship. They love each other but as a result of this incident they’re forced to examine not just who they are individually but who they are as a couple.

What was it that made you want to do this film?

I met Ray Lawrence in New York. When we met he talked about how he saw the film as a ghost story, the idea that this incident that’s taken place haunted the lives not just of the men who it happened to, but all the people on the periphery by implication. It sounded intriguing. I’d seen “Lantana” and I knew that he would make something really interesting. This is a film that makes you think about your life. I remember Ray saying to me, ‘I think you should do this film. It would be really nice if you came to Australia and did it. It would be a work experience but I think it would be an important spiritual experience for you.’ That is what stuck with me. Nobody has ever said that to me before as a reason to do a film.

What has it been like working with Ray Lawrence and his one-take process?

This is the least conventional film I think I have ever done and it is letting go of all the things that you can usually rely on. The whole thing is about letting go. It’s a scary sort of process for most actors. All the things that actors like to depend on, like make-up and lighting and so forth, the security and comfort of eight or ten takes, that’s all gone. Every actor is different. Some actors get it on the first take, others, you know, are just warming up after take five or six or ten maybe, but you don’t have that security. It allows you an incredible freedom and, ultimately, it’s your responsibility. You can always ask for another take. Ray doesn’t give much direction. He doesn’t even say action. I’ve never worked with a director who never said action before, and he usually talks about the scene after it’s over. So, yes, it’s scary. Ray will say he’s not directing the film, that he’s trying to contain what’s happened, but I think that everything, everything, in a way, comes from his vision. Ray thinks unlike any other director I’ve ever worked with, he shoots like no director I’ve ever worked with and his vision is unique to him.

Does this affect the way you approach your character?

In a more conventional approach to making a film, it is like climbing a rock, you have more places to grab hold of. Here you don’t seem to have any places to grab hold of. I think that the closer I moved to thinking about the character as myself, the more sure the journey felt. When Stewart and his friends commit this transgression they don’t even know they are doing it. They do this thing, they actually think they are doing something right, by tying up the body and leaving it in the water, but it is after they get back they realise what they have done. That has happened to me in my life. I have done something and didn’t think about the consequences of it and sometime later I realise, how could I have done that? What did I do? It is something you never forget.

What do you think people will take from this story?

Everybody, I think, comes to a different conclusion. It brings up all kinds of questions about morality and, in Stewart’s case, his marriage, and what is responsible behaviour. Guilt, regret, community, ritual, marriage, sex, love, friendship between men, friendship between women, all those issues to a greater or lesser extent are raised. The audience’s reaction to it will be complex. On the one hand you have people who will disagree with the actions of the men. On the other, people will understand it. Hopefully people will identify with the reality of the dilemma that these people are forced to confront.

screencaps

A set of lovely screencaps provided by Lozzie is in the Gallery.

reviews

Claire is the one who understands that various rituals and forms of identification and self-understanding must be gone through to achieve reconciliation with the family. And equally that these involve a change in the relationship between men and women and a reassessment of what it means to be Australian. This handsome movie is a trifle overlong and its end, though moving, slightly glib. It is, however, a work of ambition and depth. Like Lantana, it is immaculately acted and Linney and Byrne are at their considerable best.

Gabriel Byrne deserves some serious silverware for his performance in this outstanding Australian film from director Ray Lawrence (who made Lantana) and screenwriter Beatrix Christian. The movie is beautifully shot, and succeeds in being deeply disturbing and mysterious, with richly achieved nuances of characterisation. I have seen it two or three times now, and each time it gets better…

Jindabyne addresses a gulf between articulate women and moody silent males, between the whites and the patronised Aborigines, and between scared humanity and the vast and frightening landscape of Australia itself, a landcape in which one may so easily lose one’s bearings of Anglo-Saxon normality, and in which violence or loss are so terrifyingly possible. Jindabyne has the disquieting quality of Picnic At Hanging Rock and indeed the horror film Wolf Creek – which, like this film, transforms the real-life Falconio murder case. But Lawrence makes of his story something quite different: more serious, more complex, with moral shades of grey. In his boldly idealistic final scene, moreover, Lawrence ends the film on a note not of irony or despair or alienation, but forgiveness and hope. This is the kind of film to see and then talk about endlessly over dinner afterwards. It’s real cinematic nourishment.

Lawrence, whose previous films include Bliss and Lantana, works in a very specific and unusually effective way. He shoots in natural light at almost all times, and he invariably goes with only one take. “I want the words to sound like they’ve just fallen out of their mouths,” is the director’s explanation. As a result, dialogue and situations have an urgency and emotional reality that can be lacking in more conventional films.

Not all actors are comfortable with this system — but Byrne, who plays an Irish-born mechanic, and Linney, as his American wife, have made it their own. They give deeply felt, sometimes lacerating performances as one of several couples whose lives of quiet desperation are about to get a whole lot louder.

We all hold in high regard Ray Lawrence’s film Lantana. Released in 2001, it quickly became a yardstick for quality Australian cinema, a sterling example of how good local films can be when blessed with a dedicated cast, a finely sculpted script and a director with a clear vision.

However, about 20 minutes into Lawrence’s new film you find yourself reassessing Lantana as an elaborate training exercise to prepare him for this. Jindabyne is easily one of the most engrossing, thoughtful, adult-oriented big-screen dramas produced in Australia for 20 years. It is a subtle, powerful, haunting film of visual beauty, mystery and moral horror. It is not easily forgotten.

poster

More posters are in the Gallery.

listen to Kenneth Turan’s review

premiere at Toronto International Film Festival

More pictures from the premiere are in the Gallery.

interview with Gabriel Byrne

From the Jindabyne interview at CinemaSource:

…Byrne goes on to tell a story about how his life was changed by the experience of working on Jindabyne. “I tell the story simply because it is true,” he prefaces. “I’d never seen a dead body before. When my Mother died, my Father died, my Sister died and friends of mine had died I went to the mortuary and I looked at the floor, I looked at the ceiling, I looked around, I looked at everything, I looked at the chamber sheet in front of me but I did not look at the body. Part of me was kind of ashamed of that because people are told ‘you have to look at the body. You can’t be going into a Church and not looking at the body.’ I wanted to remember those people that I had been close to as I remembered them in life. I didn’t want to go to bed every night as an adult man thinking of a face done up by an embalmer to look like something that was going to haunt me. I felt that I would be haunted if I looked at that,” stressing the word haunted with conviction.

“Three months after I came back from Australia having done this scene with this body that they’d spent four and a half months researching, photographing; and those guys came up with this prosthetic body that when you touched it weighed exactly and felt exactly as a real body because they had gotten it down that kind of detail. Three months after I came back from doing the film, a friend of mine, not a really close friend but someone I had worked with, died. The husband called me up and he said ‘Listen, it would mean so much to the family if you came over to the mortuary house in Queens where the body is laid out.”

Despite initial pangs of dread, Byrne mustered up the courage to go to the mortuary and face his fears once and for all. “I said to myself, “I’m gonna do it. I’m gonna look at her face and see what it is, why it’s important to look at the face.’ So I crossed the room, I didn’t allow that moment of logic and practicality and consequence to get in the way, I just said I’m gonna do it. I walked over and looked into the coffin and I looked at her face,” he pauses with reflection. “I mean just stared at it. I came back down in my pew and I started to cry. Really cry. The husband came over and put his arm around me and said you know ‘she really liked you and was really fond of you.’”

“I walked out the door and got in the cab and I said to myself, ‘What was all that about? What was that about?’ And then I realized it taught me one of the most profound lessons of my life: that what death is, trite and all as it may sound, is the stunning absence of life.”

“And that’s what death is,” he repeats quietly to himself. “Suddenly life started to make sense to me. In eastern religions they have this thing where you cannot truly live your life unless you truly embrace death and that is the truth.”

In this world of $20 million-plus paychecks and endless commercial tie-ins, it’s becoming rarer and rarer to find actors who truly and genuinely commit to their craft. If there is one thing that is evident from hearing Gabriel Byrne talk, it’s that he truly respects his profession.

He recalls telephoning the director and professing his new-found outlook on life. “I called Ray and said ‘I’ve gone through a lot working on this film, and maybe ten people will see it,’” he adds wryly, “‘but it has made such a profound difference on my life that I can’t ever thank you enough for giving me the opportunity to do the film. Now, the way I look at it is that every kind of film I do, I say ‘I’m gonna learn something from this.’ [I’ll] work on something that will make me look at my life and figure out who I am. That’s when I realized, maybe that’s what it’s all about.”

the making of Jindabyne

part one

fan reviews

from the reviews on the IMDB page for the film:

A sublime film

24 July 2006 | by Eric Rose (Sydney, Australia)

Ray Lawrence has done it again. This film has made me see the Australian landscape in a way that I haven’t really since seeing Picnic at Hanging Rock. The feeling as the lads start on the fishing trip is somewhat Hitchcockian, since we know that we’re going to see the body sometime soon – we just don’t know when. There’s a sense of oppression and expectation overlaid on the natural beauty, that holds you transfixed.

The film may be criticised since it doesn’t try and resolve anything on a a material level. However, Lawrence is more interested in the internal lives of his characters – all of them. He also doesn’t want to hand us the exposition on a platter. There’s back-stories that are unfolded gradually, making us think about the characters as we are pointed to knowledge of what lead them to their current lives. I’m glad to see a film made for people to think about, rather than spoon-feeding us some clichés about how hard life can be for the protagonists.

Water plays a significant role throughout the movie, from the river where the fishermen find the body, to Lake Jindabyne, and the ghost stories about the drowned town. We’re made to dive into the lives of the characters, finding deeper and deeper layers of motivation as we move from the warm surface of their lives to the colder and more fragile hidden depths. We see that the body in the river acts as a sort of stand-in for each character’s transformation in a death and rebirth of the spirit.

This is another masterpiece work from a master film maker.

fan art

Gabriel Byrne Picspam: Jindabyne by Bowie28

Gabriel Byrne Picspam: Jindabyne by Bowie28

blog postings

Stella’s Posting: There Are No Bad Men Here

And this is why I think I understand Jindabyne.

Not in terms of its wide-ranging themes: death as a journey; the past now overcome by the present; men and women at odds, in conflict, disappointed, unsure; communities living side by side without knowing one another. These are philosophical concerns that permeate the film and I do not pretend here to be in command of them.

But I do think I know a bit about what it might have felt like to be in the mountains, faced with a discovery one did not want to find.

My Point Being: What’s that underneath the water?

The film paints with fine brush strokes human behaviour in times of conflict and all involved in portraying this do it impeccably. Byrne and Linney are magnificent as the complex and slightly broken Kanes. As with the Carver story, Jindabyne shows no clear demarcation between right and wrong. That was one of the brilliant things Carver could do; take an everyday situation (or in this case a tragedy) and bring it to life without casting any judgements himself.

Reverse Shot: So Close To Home

Awakening an acute consciousness of the physical environment, Lawrence imparts an impressive recognition of the pull the natural world exerts on individuals in a country defined by so much space. In doing so, he extends sympathetic understanding to the circle of men at the pivotal juncture—when they decide not to immediately hike back to report the body, but continue with their fishing plans for the next day. As the camera caresses water rushing over rocks and leaves rustling in the wind, every shot accompanied by an amplified sound mix including the buzz of bees and birdsong, the foursome—unthinkable as it may seem with a body nearby, tethered to a tree to keep her from drifting downstream—cast their lines. But, swathed in the idyllic morning light, this surrender to their surroundings seems almost acceptable; we, like them, feel transported, and are able to grasp their rationalizations: She’s beyond help; why not stay? We’ve been looking forward to this trip for weeks.

trivia

The screenplay is based on the short story “So much water so close to home” by American writer Raymond Carver. The song “Everything’s Turning to White,” by Australian singer-songwriter Paul Kelly, was also inspired by Carver’s story.

Gabriel Byrne accidentally stepped on a Brown Snake, one of the world’s deadliest, while walking through the bush one day on the set. If he’d stepped on the other end he’d have been bitten. Gabriel Byrne told the director Ray Lawrence that he was almost killed, to which Lawrence replied: “No worries mate. You would have had 24 hours…”

additional resources

Many thanks to Hugo Bruckton for the “making of” videos!